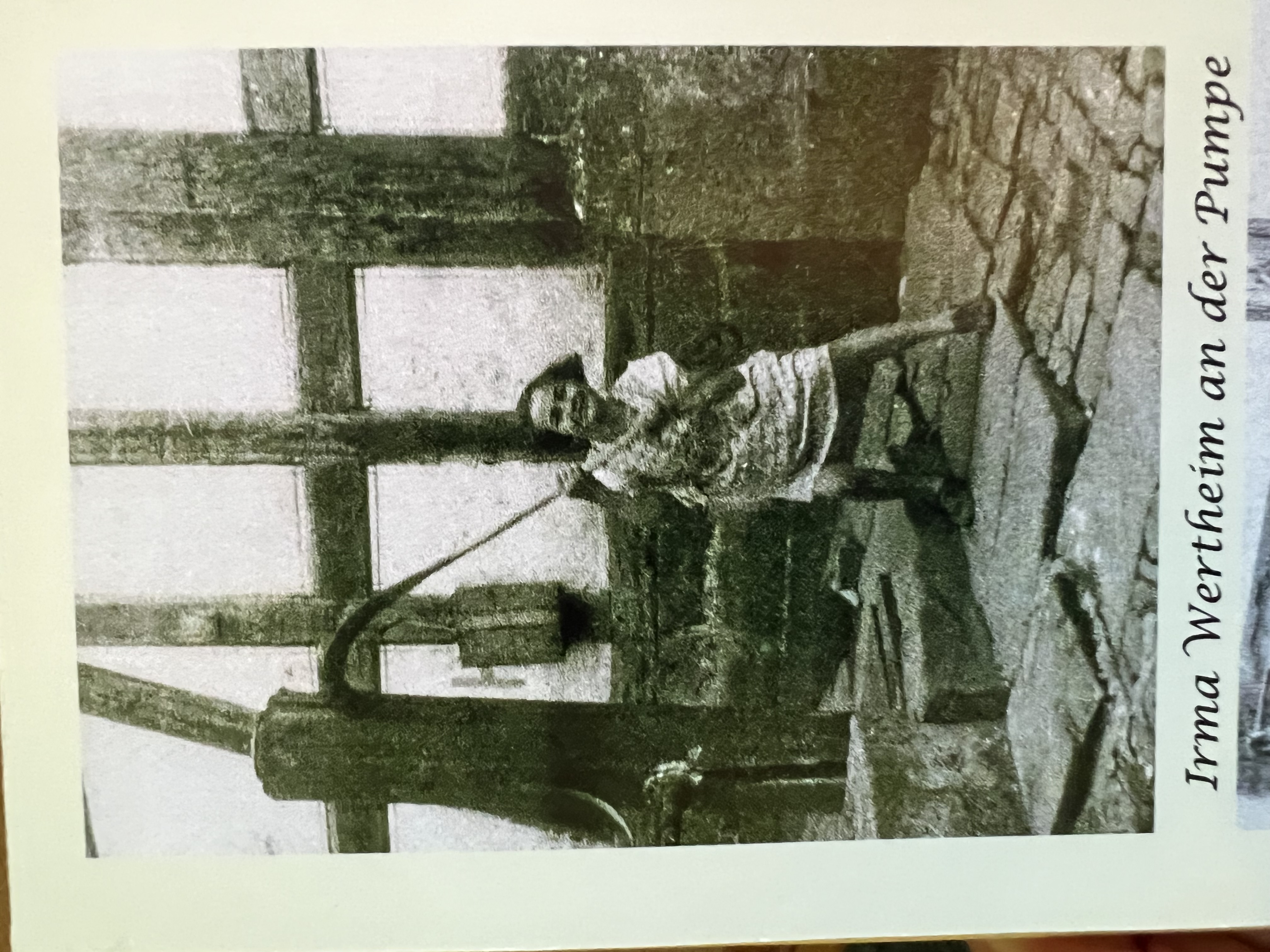

Mrs. Irma

Pretsfelder, a resident of Ranchleigh and a member of Ner Tamid Greenspring

Valley Synagogue, was born in Bürgeln, a small town in Western-Central Germany,

in 1926. “I guess that makes me an old lady now,” she quipped when I had the

pleasure of interviewing her this summer. Her family had lived in Bürgeln for

generations. She was fortunate to be able to flee Germany for England just

before World War II began, when she was almost 13 years old, and has lived in

Baltimore for the past 76 years. Her gentle and warm demeanor belies the

suffering and anguish she endured in her life. Her memory is excellent, and she

kindly agreed to provide us with her fascinating account of pre-war life in

Germany, as well as the War years in England and beyond.

ASE: Mrs. Pretsfelder, thank you for agreeing

to this interview. Could you describe for us what it was like for you growing up

in Germany in the 1920s and 30s?

IP: We lived in Bürgeln, a small village with

only two Jewish families. The closest town you might have heard of is Marburg,

which is a well-known university town 50 miles north of Frankfurt. Our house

was old, and it was built for Jews, but I don’t think my family was the

original owner. It was a large building with a sunken level, which was the

mikvah. We had one room where a part of the ceiling opened up for sukkahs.

My grandparents

lived with us, and it was actually my grandparents’ house because, in Germany,

the oldest child would inherit the house with the idea that the parents would continue

to live there, and their children would take care of them. You didn’t have

anyone going to a nursing home. Everyone was taken care of by their children.

Some were taken better care of than others, obviously, but I know from my

experience that my grandparents were very well taken care of. In fact, I

remember when my grandmother would take a nap in the afternoon, my father would

say, “You can play in here, but you have to be quiet, and if you’re not quiet,

then you’ll have to go outside – and don’t slam the door.”

ASE: Were your parents also born in Bürgeln?

IP: My father was born in the house we lived

in. My mother came from a small town called Giessen not that far away, between

Frankfurt and Marburg. Just like here, people married through a shadchan. In her town, there was only

one other Jewish family. A lot of villages only had one or two Jews. Some had

more. My father was raised Orthodox, but of course, there was no way for him to

go to shul every day because the closest shul was in Marburg.

ASE: How far is Marburg from where you lived?

IP: It wasn’t that far because my brother’s

bar mitzvah was in Marburg, and we walked there from Bürgeln. It would’ve taken

us maybe an hour. You wouldn’t go there for a daily minyan, just on Shabbos and

Yom Tov. And I think that for Rosh

Hoshana and Yom Kippur we stayed there.

ASE: How many generations back did your

father’s family go in Bürgeln?

IP: I have a friend in Germany who is not Jewish

and was born after the Hitler time. He has researched the town’s history and

found that our family was there since the 16th century.

ASE: How did your father make a living?

IP: He was a cattle dealer. We had land, which

he worked, and a few cows.

ASE: Growing up, what were your family’s

feelings toward Germany? Were they patriotic?

IP: Yes, my father fought for Germany in

Russia during World War I, in the cavalry. At first, he was in the reserves,

and then he went through the whole war. I have a picture with him on his horse.

He used to tell us kids stories about the Great War. He believed that Hashem

would not let that kind of fighting ever happen again.

ASE: You were born before the rise of Hitler. Did

you feel any kind of antisemitism as a little girl?

IP: No, not at all. But I remember the nurse

for my grandparents came, and she was so delighted when Hitler won the

election. We knew he’d written Mein Kampf,

but nobody had any idea things would turn out the way they did. You couldn’t

possibly have any idea about it. When I reached school age, I attended a

non-Jewish school, and that’s around the time that, bit by bit, things got

worse in Germany.

ASE: Was your father comfortable wearing a

yarmulke out of the house?

IP: My father always wore a cap, and my

brother always wore a yarmulke. My father never went out without his head

covering.

ASE: So, they weren’t uncomfortable showing

their Judaism?

IP:

No,

not at all. In fact, the gentiles in the area knew all about kashrus. My friends never offered me

anything to eat. When Pesach came, they wanted a piece of matzah. They knew all

about that. But then the kids started abusing me and calling me names. And, it

may sound funny, but we didn’t speak Yiddish. Not only did we not speak

Yiddish, we didn’t even know it existed. Someone asked my mother if she spoke

Yiddish. She said, “Do you mean Hebrew?” But I like Yiddish. I like Yiddish.

ASE: When did you notice the general sentiment start

to turn against Jews?

IP: I would say that it started in 1937. In

other towns, they started experiencing antisemitism earlier. In my naiveté, I went

to complain to the teacher, who had been a good friend of ours before Hitler

times. He said there was nothing he could do for me. He said to leave the

school and to, instead, attend the school in the next town that was created for

kids who could no longer attend the public schools. At the new school, there

was one teacher for all ages. My parents were hesitant to send me, but I was

forced to leave because I couldn’t handle the abuse at my school anymore.

ASE: What kind of things did the children do to

you at your school?

IP: Sort of attacking me, calling me dirty

Jew, and all those kinds of things. I went to the teacher thinking he would put

them in their place, but he didn’t, so off I went to the school in Marburg. I

had to take the train every day. The school was held in the synagogue.

ASE: Hitler came to power in 1933, but you

didn’t feel it until 1937. Did you ever think to leave Germany?

IP: We didn’t feel the antisemitism so much

in the beginning because Bürgeln was a small place, and my father was born

there. Bit by bit, it got worse. My father was really very Orthodox. He had a

lot of emunah (faith).

He said, “This will not go on; Hashem will not let this go on.” He was not

ready to leave his home. At the age of sixteen, my brother left home and went

to America because there was no future in Germany.

ASE: What was your recollection of Kristallnacht?

IP: About a year after I started the special

school, came the 9th of November 1938 – Kristallnacht. I was in

Marburg, and I saw that the fire department was out. As I got closer, I saw the

synagogue in flames. I think I just panicked, and as I was standing there – it was

a beautiful synagogue – the top fell in. I’m sorry, it’s still emotional for me

when I picture our beautiful shul burning. I ran to my relatives in town. The

police were there, and I wondered what they were doing there. Also, in my naiveté,

I thought they were blaming the Jews for setting the synagogue on fire. I took

the next train home, and I remember running up to the little yard and yelling,

“Mom, Mom, the synagogue is on fire, and they’re blaming the Jews.” This

happened on a Thursday night, and we had no idea what was happening in the rest

of Germany because we had no telephone, no communication. In the cities, they

were destroying the synagogues and also private homes. Practically all the

synagogues in Germany were destroyed except for the ones too close to

non-Jewish buildings. Then they would demolish anything inside the synagogue.

Ours was totally burned down.

I forgot to say

that, the day before Kristallnacht, we were playing in the yard of the

synagogue, and we found a bottle with some liquid. We thought, “What is this?”

The teacher called the police. They came, and then they left again. They knew

that it was some kind of flammable liquid in this big bottle. After

Kristallnacht, we realized that they were already preparing to burn down the

building.

ASE: How did Kristallnacht affect your family?

IP: We had no idea that they were arresting

Jews all over. The next morning, on erev

Shabbos, I was helping my mother clean. The policeman walked by and said to my

father, “I have to arrest you.” My father didn’t understand why. Before this,

he was a family friend. The policeman said, “I don’t know why; I just have to

arrest you and take you to the nearest town.” My mother took a big bar of

chocolate and put it in my father’s coat pocket. They took him away. On Shabbos

morning, my mother and I walked to the place where he said they were taking my

father. Of course, everyone who was arrested was gone from that town by the

time we got there. And nobody knew where they went. All they knew was that they

had all left in trucks. At this point, my brother had left home and was on a

boat to America.

ASE: Why did your brother decide to leave

Germany and come to America?

IP: We really pushed my brother to leave. I

think he would have rather stayed with us, but we convinced him that he had no

future here. You could not just go to America at that time, but we had a cousin

who was able to give him an affidavit. He got that, and he went all by himself

at the age of 16 into the unknown. I remember that, while my father was away in

the concentration camp, we got the telegram that my brother had arrived safely

in America. But at that time, we had no idea where my father was. We didn’t

know if we would ever see my father again.

ASE: Where did you go to look for your father?

IP: We went to Kirchhain, Germany, where

there were a lot more Jews. We were there for Shabbos. After Shabbos, my mother

and I took the train back to our home in Bürgeln. As time went on, we got a letter

from my father. We found out that he was in Buchenwald, Germany. At this time,

the Nazis were pushing the envelope: imprisoning Jews and seeing how much they

could get away with in Germany and internationally. We found out a few months

later that they let out the veterans, men who had fought for Germany in World War

I. My mother read this, and lo and behold, a few months later my father came home.

ASE: How did you get

him back home? Did your mother

try to free him?

IP: My mother had heard that there was

somebody in Marburg who could get him out. She told me to go there and find out

what she had to do to get him out. My mother and I were so scared, and everyone

around us was scared. In the end, there was nobody to help.

ASE: Didn’t any of your family friends who were

Gentiles help you?

IP: My father was so good to the Gentiles in

our area; he was too good to them. He lent them money. When he was in the

concentration camp, my mother and I went to them, and not one of them paid what

they owed. In fact, someone owed us money from a mortgage, and he never paid us

back. My father was just too good. My mother wouldn’t have done this. But he

grew up with these people. There was just no sense things were going to get as

bad as they were going to get.

ASE: What happened once he came home?

IP: The Nazis let the Jewish veterans out at

night so nobody would see how these former prisoners looked. We were in bed,

and somebody knocked on the door, and my mom said, “Get up!” I remember saying

to her to make sure it was really him. We were afraid of every little noise. He

came in, and he looked so emaciated, so terrible. You could hardly recognize

him. We told him to go to bed, and he said he couldn’t because he was so dirty.

He didn’t look like himself anymore. He was only in his forties, but he didn’t

live much longer after that. He never told us a thing about what went on there.

I told you before about the bar of chocolate my mother put in his pocket. On

the first day he got to Buchenwald, they gave them soup that was so salty that

the tongue would swell. He had that big bar of chocolate, and he gave a little

bit to everyone to relieve the swelling. That is all he told us about his time

in Buchenwald. All I remember is that he came home and said, “We’ve got to get

out, we’ve got to get out.” He’d seen too much, experienced too much.

ASE: How did your father get your family out of

Germany?

IP: Well, he had a first cousin who had gone

to England before Hitler came to power. We wrote to him, and he found a place

that needed workers on the farm. There was a shortage of farm laborers in England.

My father was not fit to work on the farm, but he promised that he was going to

work on the farm. It eventually killed him, but that’s how we were able to get

out.

I remember when we

left, it reminded me of Fiddler on the Roof.

Nobody said a word. I was not allowed to play with my non-Jewish friends

anymore, so nobody came to say goodbye except for one lady who lived close to

the station. She came out, and she said goodbye to us. I think about it now –

what was going through my father’s heart then. He was going to the unknown; he

didn’t know the language. But, thank G-d, he was leaving this place. I remember

so clearly going to the station with our suitcases. This was August, 1939, right

before the War.

ASE: Wow! So you got out of Germany at the last

second! How long did it take from when your father left Buchenwald to when you fled

the country?

IP: He came out of Buchenwald in ’39, and we

left the same year. It took a few months, and there was a lot to do. I thank Hashem

every day that He got us out of the jaws of Hitler. It was like a nes

(miracle), wasn’t it? But life was very hard.

ASE: Can you talk about what preparations you

and your family made before you left the only home you had ever known?

IP: You couldn’t take any money. We didn’t

take any of our furniture because we had no home to go to. We were heading to

England to live with farmers in the countryside, so we would be unable to eat

kosher once we arrived on the farm. But this was saving our lives, and we had

no other way out. Before we got on the boat, we were examined from top to

bottom to make sure we didn’t have any gold. We weren’t even able to leave with

a gold necklace. I remember we were standing naked in front of the lady. She

needed to make sure we had no gold on us. Long after the War, some people received

compensation for the gold that was confiscated. I did try to get some

compensation, but we never succeeded.

ASE: What kinds of things did you take?

IP: We were too afraid to smuggle much of

anything out. What was gold and silver and all this material stuff compared to

saving your own life? We had some of our clothes, some candlesticks for licht bentching, a beer steiner that was

given to my father from the Germany government because of his army service, and

our Mizrach picture. Someone from the government was there to watch us pack to

make sure that we didn’t put in anything that wasn’t allowed. He was a decent

guy. As a matter of fact, my mother told me to go buy a set of knives and forks

because we needed them, and while he was there, I bought that. Everything we

were taking was evaluated. But it was worth it to get your body out of there,

even if there was virtually nothing, materially, that we could take with us.

War broke out right after we arrived in England.

ASE: Did you feel relieved to be out of

Germany?

IP: Of course. Believe me, we said “baruch Hashem” many times. I remember

when we landed, as the English officials were looking through our papers, we

were whispering, and the man said, “You’re free here; you can talk out loud.”

They made us feel comfortable. We only stayed in London overnight. Then we went

to the Midlands, the place where we were supposed to work. My father began

working on the farm, and my mother was in the house. But when my father came to

the farmer to get paid for his work, the farmer said that my father should just

be glad he was out of Germany, and he ended up not paying my father.

ASE: The farmer didn’t pay him?!

IP: They took advantage of us. They were also supposed

to pay for medical insurance. They didn’t do that, either. My mother got sick,

and we had no money, so she was put where all the poor people were put.

ASE: How did you end up being placed at that

farm?

IP: The owner of the farm must have put an ad

in the paper. He had a lot of cows, and he needed help with the milking. Although

they had milking machines, you had to finish the milking by hand. That’s what

my father did. He had to sit there by the cows and squeeze. They made him work

seven days a week. There was no Shabbos, no Sunday. My father said, “This is

going to kill me.” And it did. It did. He was sick from coming from Buchenwald,

and he was now being abused by the farmer in England. Eventually, he suffered a

heart attack on the farm.

ASE: What was life like for you on the farm, as

a refugee?

IP: They took advantage of me and of our

situation. For a while, I took care of the children who lived on the farm. My

parents thought that I needed to go to school, but my schooling would be

difficult because I didn’t speak English. Fortunately, we met a non-Jewish

woman with whom my parents could speak German, and she got me into a school,

where I started to learn the new language. Soon after, I was sent to Maidstone,

England, to live with a non-Jewish family, the Weedens, where I was able to

socialize more, while also working very hard for the family. The Weedens

changed my name to Mary and made me go to church. But the church minister was very kind to me

and never pressured me to convert. Meanwhile, my parents, still on the farm in the

Midlands, were classified as enemy aliens, along with other Holocaust

survivors, and were sent to the Isle of Man.

ASE: Why were they sent to the Isle of Man?

IP: The English government panicked about the

refugees from Germany, thinking maybe they were spies. They wanted to isolate

them, so they sent them to this island off the coast of England. The America government

did the same thing when they put the Japanese into internment camps during the

War. On the Isle of Man, the men were separated from the women. My parents

didn’t have kosher food. My father had asthma, and in certain regions, his

asthma worsened. I don’t think they had doctors there on the Isle of Man, but

he needed a hospital badly so they had to release him back to England early.

Afterward, my mother also came back to the farm to be with him.

ASE: At that time where were you living?

IP: I was sent away to school in Kent, England

where I lived with a non-Jewish family. The family I boarded with thought my

parents would never make it home again, and they were going to adopt me. They very

much wanted to convert me to Christianity, but they knew they wouldn’t be

successful, so they didn’t really try – although I did end up learning their

hymns. I was old enough to know that I was a Jew, but I was in a bind. How do I

tell my hosts that I’m not going with you to church?

ASE: Didn’t the English Jews help you?

IP: From my experience, the English Jews were

not very good to the refugees. When I got in touch with a Jewish organization

about finding a place to live, they responded, “What have you been living on

until now?” They never checked on us or asked if I was being raised Jewish. It

was wartime. The individual Jews in England also just didn’t seem to do much

for the refugees, either. I’m sure some did more than others. When I lived in Kent,

there were just a few Jewish families. They knew about me and some other Jewish

girls who were boarding with the non-Jewish families there. None of the Jewish

families paid any attention to us, though. Not once were we invite for Rosh Hashanah

or Pesach, or any Yom Tov for that matter; they never offered us matzah – none

of that.

ASE: What happened after your parents came back

from the Isle of Man?

IP: After my father couldn’t work anymore on

the farm, they went to a cousin who lived near Newcastle, in northern England. I

stayed in school in Kent. When I graduated, I took a two-year course in

shorthand typing. I got a job at Meredith and Drew, a biscuit manufacturing

company which was then located in the Midlands. They were very good to me and

paid me well, so I was able to take care of my parents. I didn’t join them in Newcastle

right away because I needed to make money for them.

I worked for

Meredith and Drew until Pesach, at which time I got the news that my brother was

killed when America was fighting under General McArthur to liberate the

Philippines from Japan in 1945. The American army sent the message to my

father’s cousin, the one who brought us to England. He sent it to me because

they knew my father was sick, and nobody wanted to tell him. I had a good job,

but I left my job overnight because I had to be with my parents during this

painful time. I cried the whole way on the train.

ASE: How did your brother end up in the American

army?

IP: My brother had invented something to help

the war effort and got a deferment from the draft board. But then he enlisted,

which my parents never lived to know about. All along, we thought he was

drafted. I just found out a few years ago that he enlisted. We never saw him

again after he left Germany at age sixteen.

ASE: Did your parents end up staying in

Newcastle?

IP: My father had another heart attack

shortly after we received the news about my brother. He also found out around

that time that both his sisters and their families were killed in the War. My

mother’s mother was also killed. It was a very hard time for him. There were a

lot of siddurim where we lived in England that ended up dry rotting. I

kept one of them because it had his name in it. I opened it up, and there was a

letter inside that he wrote to his family in America.. He wrote, “Have you

heard anything about our people? I am prepared for the worst.” He never mailed

that letter, because he died soon after on a Friday night when he came home from

shul.

ASE: What did your mother do after your father

died?

IP: When my father got sick, we knew he

wouldn’t live, and my mother said, “I have to live for you now.” My father died

in 1945, the same year that my brother was killed. My father always said that

if something were to happen to him, then my mother and I should go to America;

we shouldn’t stay in England. We were in England for seven years, through the

whole War.

ASE: When you were living in England during the

War, did you and your family know about the horrors that Hitler was perpetrating

on the Jews of Europe?

IP: I remember my parents sitting by the radio

listening to all of the news about it. That’s why my father wrote in his letter

that he was prepared for the worst. I’m sure they knew. My mother was very

resilient. She went through a lot. She had two brothers. One brother was killed

fighting for Germany in the First World War. Her father died soon after. In the

Second World War, her mother was killed in Theresienstadt. She lived to see one

child killed in the First World War and the death of her husband. My father’s

parents who lived with us died a natural death.

ASE: Your mother’s mother didn’t want to leave

with you to England?

IP: It was very hard to get an affidavit for a

woman that age. My mother’s brother could have gotten out if it hadn’t been for

my grandmother. They just couldn’t leave her behind. I tell you, many people

left their parents behind. I know of a case where a family sent their father to

a nursing home in Frankfurt, where he committed suicide. My folks were not like

that. My mother’s brother’s family could’ve gotten out, but they couldn’t get

an affidavit for my grandmother so his whole family was killed in Auschwitz.

ASE: How did you get the visas to come to America?

IP: My father’s cousin, who had come to

America before Hitler, sent the visas to us. It took such a long time for

America to give its okay for us to come. Finally, I went to the American Embassy

in England. I had to stay there overnight, but when they finally saw me, I

remember telling them how my brother gave up his life for your country and

you’re giving us such a hard time. Then, things got moving.

We got here in

1946, and that’s when I started to live again. It was a seven-day trip by boat,

and I was sick most of the time. In fact, I remember that Edward, the Duke of

Windsor and former King of England, and Wallis Simpson were on our boat. They

showed their faces once and waved. When we arrived in Baltimore we got an

apartment near Shaarei Tefillah, Rabbi Drazin’s shul, a big Jewish

congregation. First, my mother worked for the cousin who gave us the

affidavits. He had a tie factory. Then she got a different job sewing, and when

she was 65, she retired.

ASE: What was it like for you to come to America?

What were your first impressions?

IP: I’m telling you, it was like I had died

and gone to Heaven. It really was. Everybody was kind to us. We had ice cream

every night. Eventually, I got married and we lived in Forest Park, right

across from the high school on Chatham Rd. My mother-in-law went to Beth

Tfiloh. My children started Hebrew school at the Liberty Jewish Center.

ASE: How did you meet your husband?

IP: Somebody set us up. I was actually going

with someone else at the time, but it wasn’t the right match so I went out with

Lou. We didn’t date too long. We were married for 66 years. In Germany I would

never have met him because he was from far away, from the town of Furth, which

is in Bavaria. Henry Kissinger was from there. My mother and I arrived here in

America around Thanksgiving in ’46, and at the beginning of ’48 I was married.

ASE: Your husband made it to America before the

War?

IP: He came by himself in 1933! He was a bit

of an adventurer. His father died in 1935, but

his family wasn’t ready to leave Germany. They were very fortunate,

though. His father was one of seven children, and they all got out. His oldest

sister went to Israel. My husband was related to the Kohns of the old Hochschild-Kohn’s

department stores, and they took good care of him.

ASE: So, you built a new life here with your

husband once you married in 1948.

IP: I’m grateful to America. People like to

criticize America. Every country has problems, but to me, it’s the best country

in the world. It took me in. Hashem gave me my family. America gave me

work. We worked hard. My husband worked

very hard – he did general home improvement – but he loved his work. He was

very handy. I continued with my typewriting. In my last job, I worked for

psychiatrists at the Baltimore-Washington Institute for Psychoanalysis. I was

there for 24 years; I’m still in touch with them.

ASE: When did you buy this house in Ranchleigh?

IP: We came here in 1961. There were only two shomer Shabbos families in all of Ranchleigh. My neighbors are

wonderful. They are very good to me. I wouldn’t be in this house anymore if it

weren’t for the neighbors. When my husband died, my children said, “I guess

you’re getting out of the house.” I said, “Give me time.” Now they don’t say it

anymore.

ASE: What comes to your mind when you think

about what you have lived through?

IP: Well, I’m close to 96. I think, “How much time is left?” But, then, I’m grateful I can still take care of myself. But all of this, everything I told you, never leaves me. In every prayer, I say “Thank You, Hashem, for saving me from the jaws of Hitler.” My