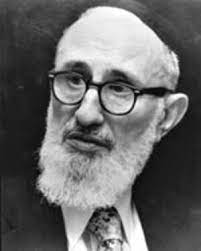

My relationship with

Rav Yosef Ber Soloveichik of Boston was somewhat different from that of his talmidim.

He had two main groups of talmidim; those who saw themselves as part of the

Modern Orthodox world and who had studied under him at Yeshiva University, and those

from the yeshiva world at large who, predominantly but not exclusively, studied

under him during the summer months in Boston. Many of the latter had also attended

his shiurim at YU somewhat clandestinely.

Let me explain the background. Rav Soloveichik, as I usually refer to him,

lived in Brookline, Massachusetts, yet he spent the midweek in New York City, where

he gave shiur at YU three times a week (Tuesday, Wednesday, and Thursday)

and also gave a shiur one evening a week at a shul further south in

Manhattan. He traveled to New York and back every week by plane. (In those days,

there was an inexpensive flight [$18] from Boston’s Logan Airport to New York’s

LaGuardia every half hour and no reservation was required. Oh, how times have changed!)

His residence was in Boston because his first and only official rabbinic position

was as Chief Rabbi of Boston. Although he was usually referred to as “The Rav,”

his personality and preference was to be a rosh yeshiva. He preferred discussion

to conclusion, the theoretical argument and its presentation to ruling.

As with many other attempts in the United States to establish a chief rabbi

in a large city, creating a position of chief rabbi of Boston was an abject failure.

Although such positions were and are always a matter of course in Europe, Israel,

and most other places, Jewry in the United States has associated rabbanus

with individual shuls, and the culture

resulting from the constitutional provision separating church from state has always

spilled over into the organization of the Orthodox communities. Even eruvin,

chinuch, and kashrus, which were always the areas of responsibility of

the city or town rav, are rarely under the control of an official citywide

rav.

A Man of Many Names

Rav Soloveichik’s appointment as the official rav of Boston did have

one lasting result. Some of his highly respected rabbinic colleagues, such as Rav

Yitzchak Hutner, zt”l, referred to him

as “The Bostoner Rav.” After his father’s passing, when he began giving shiurim

regularly in YU, this title was shortened to “The Rav,” the name by which he

is known to this day in the Modern Orthodox world. To others who knew him yet from

Europe, he was called “Rav Yosha Ber,” based on a Lithuanian pronunciation of his

first and middle name, and his extended family knew him as “Uncle Berel.”

Shiurim in Brookline

When Rav Soloveichik was in Brookline, he gave a very well attended hashkafa

shiur on motza’ei Shabbos and an in-depth Gemara shiur on Sunday

morning.

During the summer months, when YU was on vacation, he remained in the Boston

area and gave daily lengthy Gemara shiurim. He also acted as the rav

of a small shul that met in the Maimonides Day School (the first Jewish day

school in New England, which he and his wife had founded). Between Mincha on Shabbos and Maariv

on motza’ei Shabbos, he sat in his seat in the shul and answered questions of all types.

When I was home from yeshiva during summers and on Yomim Tovim, I eagerly attended these sessions.

One Shabbos Chanukah afternoon, one of the less learned members of the shul, an attorney by profession, sauntered

over to ask The Rav a “shaylah”: Why did the siddur he was using say

al hanissim at Shacharis

yet added an introductory vav at Mincha,

thus saying ve’al hanissim. The yeshiva

bachurim in the audience had difficulty not smirking. Of course, the

siddur’s publisher and proofreader were very sloppy, and someone should have

made the two versions consistent. But this was not an appropriate question to ask

one of the greatest Torah minds walking the face of the earth!

Without the slightest hint of annoyance, Rav Soloveichik asked Mr. Cohen,

the lawyer, if he chose his clients carefully. Mr. Cohen responded that he certainly

did. If the case he was to represent showed a lot of merit, there would be a good

chance of a favorable settlement and he would invest his time and skill. If the

case had poor chances, he would turn it down.

Rav Soloveichik then responded: “I also

choose my clients. Rambam and Shulchan Aruch make excellent clients. The

publisher of the siddur is not a client of mine.” Rav Soloveichik’s answer

was as true as it was beautifully expressed and respectful. Mr. Cohen had been elevated

to a comparison to Rav Soloveichik, and the reason why he was not going to explain

the siddur’s inconsistency was presented in a way that Mr. Cohen could understand

and relate to. He now knew that publishers of siddurim are not always careful

what they print and that Rav Soloveichik devoted his precious time to understanding

words written by sages whose every letter is carefully measured.