I want to thank the many people who expressed how much they appreciated my recent article about the history of our Baltimore community. In this generation, the number of strictly observant families is growing by leaps and bounds, bli ayin harah, and the younger generation, especially those who have moved here from out of town, are not aware of the history of Jewish Baltimore. History is comprised of events and dates, but history is not written in broad strokes alone; it is made by individuals. We are the beneficiaries of those who planted the seeds and whose harvest we now reap.

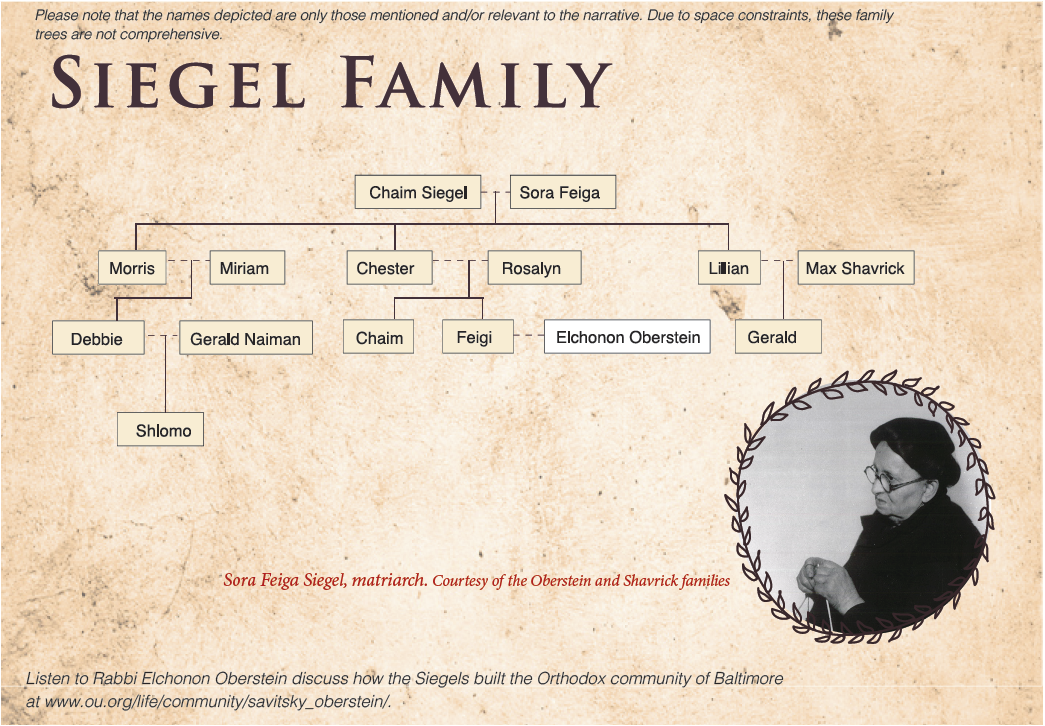

A number of years ago, at a

family simcha, our nephew Dr. Chaim Siegel of Jackson, NJ, stated that many

people in the Lakewood world he inhabits are proud of their yichus from Europe. He said that he is

proud of his yichus – that his great-grandparents

on both sides came to America long ago and remained shomer Shabbos. His great-grandparents, Chaim and Sorah Feigi

Siegel, came to Baltimore from Ponevezh, Lithuania, in the late 19th

century and raised a large family of shomer

Shabbos children.

Sorah Feigi was one of the only

women in Baltimore who wore a sheitel.

She was so tzni’usdik that she never looked

at herself in a mirror. One time, she was in a store going down on an escalator

and saw her reflection in the mirror on the side. She asked her companion, “Who

is that woman. I never saw her before.” The Siegel children had such a mother,

and she kept them on the derech.

Today, there are at least a

thousand of their progeny in Baltimore and all over the world who keep the Torah and mitzvos. Among the other frum

families in Baltimore who are descended from her are the Weinrebs, the

Shavricks, and Morris Siegel’s children: e.g.,

Sara Westreich of Toronto, the Naimans of Baltimore, and many others in cities across

the country and in Eretz Yisrael. That is the background of this article

that I share with you.

* * *

On Park Heights Avenue is

situated an unassuming little shul called the Adas. Those passing by would not about

the direct connection between this shul and a youth organization that existed

way down in East Baltimore in the early years of the 20th century,

an organization that played a big role in enabling the youth of those days to

remain shomer Shabbos. The times are

different, today, and the challenges are not the same, but if we look back at

the lessons of the past, we can gain guidance for the present.

As readers of the Where What When certainly know, I am not

from “Old Baltimore.” I am from “the cradle of the Confederacy,” Montgomery,

Alabama. But I have a reason to look back at the early years of the Adas. For

more than half a century, I have been privileged to have some connection through

my aishes chayil. Feigi’s parents,

Chester and Rosalyn Siegel, of blessed memory, along with other members of the

Siegel family, were active leaders of the Adas organization and influenced many

teenagers as well as children, who became the ancestors of frum families in Baltimore and beyond. Between our own children and

those of Feigi’s only brother Chaim, there are many descendants named Yechezkel

and Rivka, for Chester and Rosalyn, but there are also hundreds of other

families whose very connection to Yiddishkeit is owed to what they and others

did in East Baltimore before World War II.

I thought it

would be worthwhile to try to convey to our own growing “tribe,” bli ayin harah, of Obersteins and Siegels

– the great-grandchildren of that

generation – as well as to the many “newcomers” whose roots are not in the

Baltimore, something of the lives and times of those who laid the foundation

for what we take for granted today.

Trying to

explain the “olden days” to a young person is not simple. These children probably

don’t know what a rotary dial telephone is or how to use carbon paper on a

typewriter. How can they understand a bygone era? Not only that, but they have

all grown up in communities where being mitzvah-observant and pursuing Torah

learning are the norm. How then to put into perspective their great-grandparents’

role in the rebirth of Torah in Baltimore and beyond? To them, a spiritual

giant is someone you read about in an ArtScroll biography. How then can I show

them the absolute spiritual heroism of their great forbearers?

* * *

Many years

ago, I interviewed two couples who knew Chester and Rosalyn back in the 1930s

and ’40s. I felt that talking to people who have vivid memories of those times

would help us all understand what it meant to be a frum Jew, especially a shomer

Shabbos, in those bygone days. Chester and Rosalyn were by no means the

only ones, and they operated within an organization, but in focusing on them, I

am also recalling the nisyonos, the

challenges, all young Jews faced. They are exemplars of that era.

Matthew Bennett, of blessed memory, was one of

the elders of Shomrei Emunah. One day, he told me that not only was he at my

wedding, but he held a pole of the chuppa

at the wedding of Chester and Rosalyn Siegel back in 1931. Here are his

recollections:

“I was born in

Baltimore in 1919. My father had learned in the Telshe Yeshiva, where Rabbi

Gordon was his chavrusa. My father

was a shochet and also operated a

Hebrew school in our home at 2101 East Baltimore Street. He also taught at TA.

Among his students were Rabbi Aaron Paperman, Rabbi Avigdor Miller, and Rabbi

Manuel Poliakoff. Rabbi Chaim Schwartz told me that my

father was his father’s alef beis rebbe.

He remembers that, once in a while, someone would bring a chicken into the classroom.

My father would have to go out and shecht

the chicken and then come back and teach the children with bloody fingers!”

Matthew’s wife,

Sylvia (née Baker), was also born in Baltimore and lived at 19 North Broadway.

Her father was a cap maker, and then he bought a gasoline station. Both Matthew

and Sylvia belonged to the Adas as youngsters. This is how Mr. Bennett

describes the Adas: “Chester and his older brother Morris, as well as O.D.

Taragin and a number of other young people, were afraid that Yiddishkeit was

dying out in East Baltimore. They founded an organization for the young people

whose motto was ‘Judaism in general, Shabbos in particular.’ The week they

started it was Parshas Vayakhel, which

starts ‘Vayakhel Moshe es kol adas bnei

Yisrael – And Moshe gathered the entire congregation of the sons of Israel.’

Therefore, they decided to call their club the Adas. They started a shul, and

it was called ‘the boy’s shul’ because it was entirely run by the younger

generation.

“In order to

keep the youngsters interested, they had groups,” continued Mr. Bennett. “There

were the seniors, intermediates, juniors, and sub-juniors. I was in the

intermediate group, for kids around 13 to 16. The groups would meet Shabbos

afternoon at a larger shul, the Tzemach Tzedek, which was a Lubavitcher shul headed

by Rabbi Axelrod. It was located at Collington and Fairmont Avenues. In the

beginning, the groups were coed. Velvel Taragin (Alan’s father) and Sam

Krevitsky led groups. I think Chester led the Junior group, ages 10 to 13.

“The kids

would come back to the Adas or to various homes on Shabbes nacht for activities,” said Mr. Bennett. (No one called it motzoei Shabbos in those days.) “Every

Lag b’Omer we had a hayride. There were about 20 kids in each group, mostly,

but not all, from frum homes. Once a

year, there was the boat ride to Tolchester. Rabbi Teddy Davis came back from

Slabodka and split the co-ed groups, but that happened a little later in the

story.

“Rosalyn came

from Altoona, Pennsylvania. She was a shomer

Shabbos girl growing up in a small community where few, if any, were as

observant. She came to visit family in Baltimore and met another religious girl

(later, Eugene (Pitzy) Siegel’s mother). She told Rosalyn that the religious

kids all congregated at the Adas, and she brought her along to a meeting. At

that first visit, she met Chester. She spent the summer in Baltimore, and

Chester courted her by taking her on the Adas hayride and the Tolchester boat

ride. He wanted to marry her then, but she decided to return to Altoona and

finish her senior year of high school first. I remember they got married

outside, in front of the Adas, and the Intermediate boys were the ones who held

up the chuppa. I was one of those

boys.”

Mr. Bennett

added, “At this point, it is important to clarify that there were no Bais

Yaakovs in the United States and very few boys schools either. The Talmudical

Academy only went to the sixth grade in my youth. Those boys who wanted to

learn more would have a class with Rabbi Hyman Samson, the Rosh Yeshiva of TA,

after public school. It was a different world. Only a few youngsters were shomer Shabbos, and it was hard to find

employment. Keep in mind that these were the years of the Great Depression. The

Adas was unique. Morris Siegel was the leader of the Adas, and he and others

strove mightily to help young American boys and girls find shomer Shabbos jobs. Morris’s grandchildren, the Naimans, are

important members of the Baltimore community.

“As time went

by, more and more of the original Adas activists joined the move uptown.

Morris, who was the prime mover and leader, moved near Shearith Israel on

McCullough Street. Chester and Rosalyn remained in East Baltimore, and they

were the main ones keeping the Adas going. One reason they were able to devote

so much time to the Adas was because they had no children. They were married in

1931 and did not have a child until after Chester came back from the army after

World War II. The birth of Feigi in 1950 was some simcha. The whole Orthodox

community was so happy for them,” concluded Mr. Bennett.

* * *

At the end of Parshas Balak, the Torah describes a

terrible moral breakdown, especially among the youth. At the moment of the most

brazen behavior by Zimri, Pinchas acted. He is described as a kanai, a zealot. As for the people’s

reaction, the Torah uses the following phrase: “Ve haimoh bochim pesach ohel moed – And they cried at the entrance

to the Tent of Meeting.” As Rav Dessler explains, “When people are swept up in

the spirit of rebelliousness, any attempt to stop them will only incite them

further. Therefore, they were reduced to helpless weeping.” This thought

describes the sense of helplessness felt by many frum Jews at the beginning of the 20th century here in

Baltimore. For many, there was a sense of yei’ush,

despair. Could anything be done to inspire young American boys and girls to be shomer Shabbos?

What is a kanai? I am sure the youngsters of the

Adas were called fanatics by those who thought that they were too strict. Rabbi

Dovid Katz suggested to me that a better translation for kanai is “passionate.”

* * *

I want to

share with you the recollections of an Adas girl from those years, Ann Cohen,

of blessed memory. Here are her own words: “The Adas was the love of my life.

We spent hours at the Adas. One day, when my father, who was a chazan, was still alive, I came into the

house and heard him talking to my mother about moving uptown. I started to cry;

I told them that I only would move if we moved next door to the Adas. When I

was 10 years old, I started Hebrew school at the Adas. We learned five pesukim at a time, and for homework we

had to be able to read and translate those five verses into Yiddish. Rabbi

Davis’s wife was our teacher. On Shabbos, we would learn Pirkei Avos. We went in the morning and then returned for Mincha.

“I remember

how, one day, Rabbi Davis drew a tree on the board and said that some mitzvahs

are higher than others and that we had to separate the boys and the girls from

then on,” continued Mrs. Cohen. “This is a later period than that of Matis and

Sylvia Bennett, when the shul had a rabbi who guided them in halacha. Not

everyone went along with it, and there were some mothers who pulled out their

girls, but I stayed. Rebbetzin Davis was a major influence on my life.

Everything she taught me has stayed in my mind.

“We used to

come back to the Adas on Shabbese nacht

and play on the sidewalk outside, games like hide and seek. You could stay

outside until midnight and not be afraid. Rosalyn Siegel was our advisor and our

role model. She was a beautiful woman, with honey blond hair pulled back in a

bun. I think that makes an impression on a young girl. She and Chester made a

beautiful pair. They were the glue that held the Adas together.”

Morris Cohen

added at this point that “Chester and Rosalyn were the pnei of the Adas.” Translating that phrase is not easy. Literally,

it means that they were the “face” of the Adas; when you think of the Adas in

those days, you think of them.

Ann remembers

that once there was a melave malka and Rosalyn assigned her to

memorize and recite in Yiddish a story about why the dog chases the cat and why

the cat chases the mouse. All the parents came, and she was very proud to be

able to recite it in Yiddish. When I told this to Feigi, she remembered that

her mother had that book in the basement. Unfortunately, I don’t think we saved

it for posterity. Ann says, “We were lucky; we were a small clique of shomrei Shabbos.”

* * *

It would be a

travesty to write this history to make it conform to the norms of 21st

century Orthodoxy. These boys and girls were the few among the many, the ones

who did not submit. The world they grew up in was far different from the one

their great-grandchildren have the zechus

(privilege) to live in today. They fought for basic Yiddishkeit: for Shabbos

and kashrus. They did not battle

gentiles but other Jews who laughed at them and called them foolish for

persisting in the old ways. Ann and Morris Cohen told me that they were laughed

at by their friends, people from the same East Baltimore neighborhood but who

had no connection to the Adas. Their friends ridiculed them for keeping kosher

when they went out together.

I do not

pretend to understand the ways of the One Above. When I told Feigi that the

reason her parents were able to devote their time to the boys and girls of the

Adas was because they were not blessed with children for so many years, my

righteous wife said, “Maybe the reason Hashem did not bless them with children

earlier was so they could influence those children.”

There is much

more that could be said, but I want to wrap this up with a thought from the

Ksav Sofer. I was discussing this topic with Rav Aharon Tendler of Ner Yisrael,

and he showed me a beautiful comment by the Ksav Sofer. “In Parshas Lech Lecha, the Torah tells Avraham,

‘Lech lecha mei’artzecheha…va’escha legoy

gadol – Go out from your birthplace…and you I will make you a great

nation.’ Rashi explains,

‘Here you were not zocheh to have

children, but there you will have children.’ The Ksav Sofer explains that there

is a reason why Avraham and Sarah did not have children right away. He says, ‘If

they had been blessed with children, they would have been busy raising their

own family and would not have had time to learn with others,’ the converts that

they brought to believe in Hashem.”

Is there any

connection between the early Adas and today’s burgeoning frum Baltimore community? That is for you to decide. The challenges

we face today are not identical to those Ann Cohen faced. Ann remembers that

she and another frum girl wanted to

be excused from class when they were singing Christmas carols, but the teacher

would not let them leave. Ann said that she sat in the back and silently

translated the songs into Yiddish to while away the time: “Shtile nacht, heilige nacht.”

Perhaps the

greatest challenge we face today is keeping our children on the derech, passing our traditions on to the

next generation, and motivating them to live by the ideals of their ancestors.

We have a promise from Hashem. At the end of days, Hashem will send back

Eliyahu, who also was a kanai, one

who was zealous for Hashem. “Vehashiv lev

avos al banim velev banim al avosam – He will return the heart of fathers

to the children and the heart of children to their fathers.”