“Do not scorn any

person….for you have no person without his hour.” (Avos 4:3) The Rambam

interprets Ben Azzai’s dictum as follows: It is wrong to mistreat anyone who

may be of lowly status because the time will certainly come when such person

will rise to a position enabling him to seek revenge. This mishna does not imply that it would ever be otherwise acceptable to

malign or mistreat another. It simply provides an additional reason to avoid such behavior, namely, that the

perpetrator may well find himself one day at the mercy of his victim.

The Talmud

Yerushalmi relates the following relevant incident: Some Jews were once abusing

a lowly swineherd named Diocletion. Consequently, Diocletion rose to become emperor

of the Roman Empire, and, recalling his previous humiliation, he devised a plan

to exact retribution against the Jews. Accordingly, he formulated severe

decrees and pogroms. The chachamim

thereupon appeased Diocletion, narrowly averting catastrophe. Similarly, the

people of Gilead banished Yiftach only to eventually turn to him for help and

leadership in their hour of need. (Shoftim 11:1-11)

What interests me

most in this mishna is not the

revenge aspect but the concept of a person rising from humble status to a position

of greatness. I have not come across any mishnaic commentary that explains what mechanisms other

than hashgacha pratis may operate. However,

it is instructive to peer into the lives of three contemporary individuals,

each of whom rose from relative obscurity to achieve genuine fame and glory in

times of massive upheaval and war. In so doing, it may be possible to unravel

this mystery.

Tuvia Bielski: 1906-1987

As is generally

well known, Tuvia Bielski, together with several younger brothers of his, led a

band of Jewish partisans who hid in the forests of Belorussia during the Nazi

occupation of World War II. From 1942 until 1944, they endeavored to save as

many Jews as possible from the jaws of death by creating the closest thing to a

safe haven deep in the forests. For the most part, they left direct military

confrontation to the Russian partisan forces, while developing a remarkable

infrastructure for the benefit of all refugee men, women, and children. A school,

hospital, nursery, field kitchens, bakeries, various skilled workshops, a shul

and a mill all existed deep in the forest. In addition, they provided tailoring

and cobbling services for nearby Russian units. Of course, they resorted to

forced requisitioning of food and supplies from local villages, as needed. It

is estimated that Bielski saved the lives of 1,200 Jews.

Contrast this heroic

existence with snippets from the relatively humble life Tuvia led both prior to

and after the war. From 1927 to 1928, he served in the Polish army and achieved

a rank of corporal. After discharge, he rented a mill to add to his family’s

income, but it proved to be inadequate for their needs. After the war, he moved

to New York and ran a small trucking business for 30 years. He died nearly penniless

in 1987.

Oskar Schindler: 1908-1974

A Czech

industrialist, Schindler joined the Nazi party in 1936 and was soon recruited

to serve as a spy for their military intelligence services (Abwehr). He arrived

in Krakow in October, 1939 on government business, but, ever the opportunist,

he shortly struck out on his own. By the end of 1939, he had acquired a local

enamelware factory then held in receivership, renaming it Deutsche

Emailwarenfabrik (DEF). As portrayed in Steven Spielberg’s landmark film, Schindler’s List, Schindler, who chose

to employ mostly Jews, gradually morphed from a highly successful,

profit-motivated entrepreneur to a dedicated savior of Jews. He personally

witnessed the destruction of the Krakow ghetto early in 1943 and was

traumatized. At that point, he resolved to do everything in his power to

protect his Jewish workers plus any additional Jews he could bring into his

factory. It is mind-boggling to even contemplate what courage and tenacity this

man had to hone in dealing directly with his fellow Nazis to achieve this goal.

Schindler, over time, used the vast wealth he accumulated to finance bribery;

black market purchases of supplies; additional construction costs of a co-op,

dining facilities, an outpatient clinic; plus several moves, all for the

benefit of “his” Jews.

By October, 1944,

in the face of advancing Russian troops, Schindler arranged and paid dearly for

the wholesale transfer of his entire Jewish workforce to the relative safety of

Brunnlitz, located in the Sudetenland. There, he established a munitions

factory but adamantly refused to produce artillery shells of any use. Instead,

and at great risk, he resorted, once more, to black market purchases – of finished

product – to fulfill production quotas. By war’s end, his vast wealth was

virtually exhausted. Like Bielski, Schindler saved an estimated 1,200 Jews.

Any study of this

man’s life in the pre- and post-war periods, in contrast with the above, leaves

one absolutely bewildered and stunned. From approximately 1928 to 1938, he held

a series of decent but unremarkable jobs. As an agent of the Abwehr, he was

arrested by Czech authorities, in 1938, on espionage charges and briefly

imprisoned. By this time in his life, he was already beset by drinking problems

and chronic debt.

Schindler’s post-war

life was similarly pockmarked with epic failure after failure:

·

From 1945 to 1949, the Schindlers

got by on monetary assistance provided by Jewish organizations. In 1948, he

submitted a reimbursement claim for his wartime expenditures totaling

$1,056,000 to the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee. He received

only $15,000.

·

From 1949 to 1958, the couple lived

in Argentina, where they operated a chicken and nutria farm. The venture went

bankrupt in 1958, whereupon Oskar left his wife and returned to Germany.

·

Between 1958 and 1963, he engaged

in a succession of unsuccessful enterprises, including a cement factory. He

declared bankruptcy in 1963 and was stricken with a heart attack in 1964.

·

For the remaining 10 years of his

life, he subsisted on donations from Schindlerjuden, the Jews he had saved, the

world over.

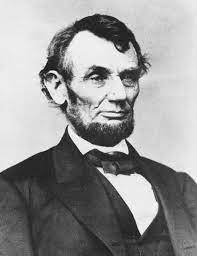

Abraham Lincoln: 1809-1865

Our 16th

president, Abraham Lincoln, is unquestionably one of our greatest presidents.

He[E1] led the nation in

its highest moment of peril, the American Civil War. Throughout the bloody

conflict, Lincoln conducted the war, emancipated the slaves, and, in the end,

preserved the Union, each a remarkable feat. Unlike Bielski and Schindler, most

of Lincoln’s prior life and political rise was marked with success. However,

his career was so punctuated with setbacks that it is instructive to recount

them here:

·

In 1832, Lincoln purchased a 50%

interest in a general store in New Salem, Illinois. The business soon

floundered, and he subsequently sold his share.

·

He was then appointed to township

postmaster, where he compiled the worst efficiency record in the county.

·

Entering politics, Lincoln ran for

the Illinois general assembly. He lost.

·

In 1843, honest Abe ran for a seat

in the U.S. House of Representatives. He lost the Whig party nomination. However,

he subsequently won the nomination and the election in 1846.

·

While working on a committee in the

War Department, Lincoln cosponsored a bill to conditionally abolish slavery in

Washington, DC. The bill failed to garner any support within his own Whig party

and did not advance.

·

He opposed President Polk’s

Mexican-American War policies, but several resolutions he proposed were ignored

in Congress.

·

In 1849, under President Zachary

Taylor, he lobbied to be appointed commissioner of the General Land office. When

his efforts failed, Lincoln quit politics and resumed his law practice.

·

In 1854, Lincoln ran for U.S.

Senate and lost.

·

At the 1856 new Republican party convention,

Lincoln received some notable support to run as vice-president. However, he

lost out in his bid to William Dayton.

·

In the 1858 U.S. Senate election,

Lincoln and Stephen Douglas held a series of famous debates over the

institution of slavery. Though the Lincoln candidates won the popular vote, the

Democrats won more legislative seats, and the incumbent Douglas won

re-election.

Abraham

Lincoln unfortunately never returned to obscurity because, assassinated in

office, he didn’t live to experience a post-presidency.

How on earth could

such relatively mediocre men achieve meteoric success, however fleeting? Truth

be told, I still don’t know, leaving the mishna

in Avos an enigma. However, I strongly believe there exists a common thread

that enables an average or weak person to soar out of the clutches of his or her

“limitations.” That element is known as a sense of “self-worth.” In the

parlance of mental health specialists, there is a clear distinction between

self-worth and the more common term, “self-esteem.” As important as self-esteem

may be, it is predicated on achieving some success and sustaining it. The

moment one fails in some endeavor, that sense of self-esteem is punctured or

nullified. On the other hand, self-worth involves a positive estimation of one’s

core or essence, not one’s actions. Hence,

although I may have faltered, the error reflects something I did, not who I am. Everyone makes mistakes in life. In order to learn from them

and move on, it is crucial to hold fast to an ever-present sense of self-worth.

This, I believe, is a prerequisite for the phenomenon of catapulting an

ordinary person (including the aforementioned gentlemen) to extraordinary heights.

[E1]I

added this because you never actually say that he achieved greatness.